|

The Reichstag of the Holy Roman Empire The Reichstag was, in modern terms, the legislative body of the Empire. It should not be thought of as a representative institution in the modern sense, because many individuals and communities were not represented in it, yet its decisions were binding on all subjects of the Empire, and it was the only institution with which the Emperor dealt. The composition of the Reichstag evolved over the Middle Ages. By 1495 it had been divided into three colleges or sections:

A. The States of the Empire A State of the Empire (Reichsstand, status Imperii) was a member having a seat and a vote at the Reichstag (Sitz und Stimme). The corresponding adjective is reichsständisch. A few imperial officers, such as the hereditary marshal (Pappenheim) and the hereditary usher (Werthern), had seat without vote, and as such were not reichsständisch (Pappenheim, however, was able to obtain recognition as a mediatized family in Bavaria in 1831). The status of State of the Empire was originally attached to a particular land, and was a right of the owner or ruler of that land. Consequently:

Since 1653, admission to the Reichstag was not solely dependent on the emperor's will, but required qualification and cooptation by the Reichstag. The requirements were up to the individual colleges. Actual exercise of the rights to sit and vote was not necessary.

Since 1653, the Emperor was forbidden in principle from making individuals into states (so-called reichsständische Personalisten), without the possession of a territory (an imperial knighthood was not enough). There were exceptions, however:

After qualification and cooptation, the quality of State of the Empire was retained, whether or not the cooptation was followed by a formal admission, whether or not the seat was taken or the vote exercised. A territory could lose the quality of State of the Empire

The privileges of the States of the Empire, guaranteed by the Wahlkapitulation, were:

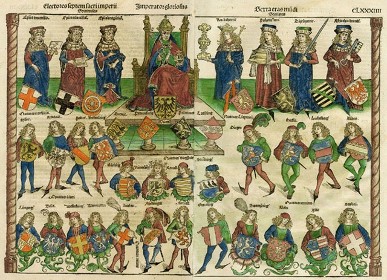

B. The Electors The Emperor was chosen by the Elector princes (Kurfürsten). This institution emerges sometime in the first half of the 13th c., as a consequence of the crisis of 1198. It appears in the Sachsenspiegel, a compilation of German feudal law written between 1220 and 1235. Its composition seems to have been set fairly early, by the 1230s at the latest. Initially the electors nominated a candidate, subject to ratification by the magnates, but fairly quickly their choice became final. Its formal regulation came with the Golden Bull of 1356, although changes were made occasionally. by the late 15th c., the electors were understood to form a distinct college. The composition was set as follows:

The Council was presided by the archbishop of Mainz, who had precedence over all electors. The status of the king of Bohemia was controversial for a long time, because he was not (necessarily) German; on the other hand, he was the Butler of the Empire, and one theory founded the right to elect the Emperor on holding one of the four high offices. One view was that the king of Bohemia's vote was meant to be the deciding vote in case of an even split of the other six. The Sachsenspiegel did not include him as an elector, but the Schwabenspiegel did. It took the Golden Bull of 1356 to settle the matter definitively. The king of Bohemia did not attend the elections after Wenceslas in the 14th c., and in the 17th century was not present for the deliberations, until 7 Sep 1708, when Bohemia was admitted again as a full member of the Electoral college. Changes to the list of electors were made in the 17th and 18th c.

The number of electors was set at 7 in 1356, changed to 8 in 1648, 9 in 1708, 8 in 1777, 6 in 1801 and 10 in 1803. The powers and rights of the electors were:

Elections and Coronations The electors elected the king of Germany or king of the Romans who, once crowned, became the Emperor. Under the Habsburgs, it had become usual for the Emperor to have his oldest son crowned as king of the Romans. At the peace of Westphalia, France and Sweden tried to have the right to elect the king of the Romans transferred to the Reichstag, without success. Finally, the electoral capitulation of 1711 included the stipulation that an election would take place only in case of extended absence, advanced age, permanent incapacity of the Emperor, or other urgent necessity. It was up to the electors to decide to hold an election. They were obligated to give the emperor prior notification, but could proceed without his approval. The electors were free to elect whom they wished, and the Emperor, in his capitulation, promised not to interfere with this freedom or use any form of coercion. They could, nevertheless, pledge their vote: when Brunswick (later Hanover) was given an electorate in 1692, it promised in return never to vote for anyone else but the eldest-born archduke of Austria. (In the election of 1742, there were none, and the elector of Hanover was free to cast his vote). A spiritual elector could vote even before having been invested by the Pope and received the pallium, as long as he had been invested by the Emperor. Conversely, an archbishop deprived of his electorate but not of his see could not be replaced as elector and his vote was forfeited (as happened to Cologne in 1711). A minor's vote was cast by his tutor. The electors were summoned by the archbishop of Mainz, or else by the archbishop of Trier, normally within a month of the death of the Emperor. The electors met in Frankfurt, as prescribed by the Golden Bull (when they didn't, the city protested and it was granted reversals reserving its rights for the future) normally within three months of notification. The Grand Marshal was responsible for the logistics and protection of the electors and their suites. Electors appeared in person, entrusted their vote to another elector, or more often sent an electoral embassy, even if they were present (as the king of Bohemia in 1657 and 1690, or the elector of Mainz in 1741). The ministers presented their credentials to the archbishop of Mainz, who presided over the deliberations, in particular the drafting of the electoral capitulation. When the moment to vote came, the Grand Marshal ordered all princes, noblemen, ambassadors, representatives etc. not part of an electoral suite out of the city. The electors proceeded on horseback from the city hall to the cathedral, and convened in the electoral chapel, and swore to choose the worthiest man, and to accept the majority vote. The elector of Mainz proceeded to collect the votes, starting with Trier and ending with Saxony, and then himself. Electors could vote for themselves, as the king of Bohemia frequently did (although formally, a majority voted for him and he then consented). The candidate receiving more than half of the votes was elected. In modern times the votes were unanimous. However, some elections were contentious. The election of 1519 was one. As early as 1516, while Maximilian was not clear about his own intentions for his successor, the king of France François I had begun collecting votes, and by 1518 secured the votes of Trier, Mainz, Brandenburg and the Palatinate. Then Maximilian decided to have his grandson Charles elected before his own death, and soon had the commitment of Brandneburg, Cologne, Mainz and the Palatinate, with the vote of Bohemia (the minor king Louis II) cast by his guardians Maximilian and the king of Poland. With Maximilian's death all bets were off and negotiations began anew. Here, the order of voting mattered, and allowed electors to make conditional promises: thus, Joachim of Brandenburg (who voted 6th) could promise to vote for François if two electors had voted for him and if he knew that his brother the archbishop of Mainz (who voted last) would also vote for him. In the end, Charles secured enough votes to win the election, in part through payments to the electors (330,000 florins in lump-sum payments and a total of 30,000 florins in annual pensions promised to four electors). What happened on June 27 (when the voting began and broke off after an hour) and June 28 is unclear; there is a possibility that Frederick the Wise of Saxony was elected but declined. In the end, all electors voted for Charles, although the elector of Brandenburg made a notarized statement beforehand that his vote was not free. (see Henry J. Cohn, 'Did Bribes Induce the German Electors to Choose Charles V as Emperor in 1519?' German History 19(1):1-27.) Another contested election was that of 1741. Karl VI had died in 1740, the last male Habsburg: there was no obvious successor for the first time in over two hundred years. In 1741 the electors decided to exclude the ambassadors of Karl's daughter Maria Theresia, queen of Bohemia, not because she was a woman but because of the pending dispute over that crown (the elector of Bavaria had just seized Prague and had himself crowned king of Bohemia in December 1741). She protested against the legality of the election until the treaty of April 22, 1745 with Bavaria, by which she posthumously recognized Karl VII as emperor. At the election of 1745, she voted, but the electors Palatine and of Brandenburg abstained, although the elector of Brandenburg later recognized the validity of the election on Dec. 25, 1745. Once elected, the candidate was asked by the archbishop of Mainz if he accepted the election capitulation drafted by the electors (until 1708, the ambassadors of the king of Bohemia were shown the draft beforehand in an adjacent room). If he did, he was immediately proclaimed in the cathedral. In the elect's absence his ambassador or representative took the oath, but the imperial government remained in the hands of the vicars until the elect had taken the oath himself.The procedures for electing a king of the Romans were identical, except that the king-elect swore not to intervene in the affairs of the Empire. The Golden Bull prescribed that the German coronation take place in Aachen, although in modern times it usually took place in the same city as the election. According to an agreement of 16 June 1657, included in the Wahlkapitulation of 1658, the ceremony was performed either by the archbishop of Cologne or the archbishop of Mainz, according to whose province was the location of the coronation (Frankfurt was in the province of Mainz); and if it took place outside of either province (for example, Regensburg, in the province of Salzburg) then Cologne and Mainz alternated. The insignia used in the coronation consisted of the crown, the silver scepter, two rings, a gold orb, the sword of Charlemagne and the sword of Saint Mauritius, various clothes, an illuminated Gospel, a sabre of Charlemagne, and a number of relics (the tablecloth of the Last Supper, the cloth with which Christ washed the feet of the Apostles, a thorn of his crown, a piece of the Cross, the spear that pierced his side, a piece of his crib, the arm of Saint Ann, a tooth of John the Baptist, the blood of Saint Stephen). These insignia and relics were kept in Aachen and Nürnberg and sent to the coronation. The emperor was crowned by either the archbishop of Mainz or that of Trier, depending on the diocese in which the ceremony took place (in 1742, the archbishop of Cologne, brother of Emperor Karl VII, officiated with the consent of the archbishop of Mainz). All three spiritual electors laid together the crown on the emperor's head. After the election the emperor was made a canon of the cathedral of Aachen. He then proceeded to the city hall for the banquet.

The following table is incomplete.

C. The Princes The second college of the Reichstag was composed of the princes, counts, lords and prelates who ranked as states of the Empire (Reichsstände). Not all were members of the college, or even directly represented. The composition of the assembly varied before it was formally organized; after 1489, however, no further increases were possible without a majority vote, and the membership list was formally set in 1582. The Council did not operate on a one-man one-vote principle. Accordingly, there were individual votes (Virilstimmen) and collective votes (Curiatstimmen). The Council of Princes (Reichsfürstenrat) included both clerics and lay people. Clerics, as in other European Estates such as the House of Lords in England or the Estates General, had a seat by virtue of the see or abbacy. Those prelates who did not have individual votes were grouped into two benches, the Bench of the Rhine and the Bench of Swabia, each with a collective vote. The secular princes included the Princes (Fürsten) properly speaking (with titles of prince, grand-duke, duke, count palatine, margrave, landgrave) and the Counts and Lords (Grafen und Herren). The princes held individual votes (although sometimes held collectively by a family) while the counts and lords were grouped in Benches, each bench with one collective vote. The bench of Franconia was created in 1630-1641 from the bench of Swabia, and the bench of Westphalia was created in 1653 with part of the bench of Wetterau: thus, after 1653, there were four benches. Until 1582, votes at the Reichstag were owned by individuals, and were often multiplied when inheritances were divided, or, more often, jointly held by several families. After 1582, votes were attached to a territory (in a few exceptional cases a vote was granted to an individual without territory), and were no longer multiplied, but could still be shared by various individuals (as result of an inheritance, typically). By 1792, there were 100 votes in the Council of Princes, of which 55 were Catholic (although Osnabrück alternated between Catholic and Protestant since the peace of Westphalia). Of the 100 votes, 37 were clerics (35 individual votes and 2 collective votes), while 63 were lay (59 individual votes and 4 collective votes). (See the detailed composition.) The peace of Lunéville of 1801 led to the elimination of 18 votes in territories ceded to France, almost all of them Catholic. Plans to redistribute votes floundered on the issue of maintaining the religious balance, and although a special committee of the Reichstag had reached and agreement in 1803, the Emperor had not yet ratified it by the time the Empire dissolved in 1806 (see below). Secular votes in the Council of Princes, 1582 The following table (based on Arenberg 1951) lists the secular votes in the Reichsfürstenrat in 1582, the decisive moment when allocation of votes became determined by strict rules. The families who possessed those votes in 1582 are considered Hochadel: altfürstlich for the princely families, altgräflich for the comital families. Families who were elevated between 1582 and 1803 to princely (resp. comital) rank, with membership in the Council of Princes, are termed neufürstlich (resp. neugräflich).

Evolution of the Council of Princes from 1582 to 1803 With the peace of Westphalia in 1648, 9 ecclesiastical territories were secularized (the word was coined by the French delegation at the Westphalia negotiations), and the corresponding votes transferred to the Reichsfürstenrat, in the hands of the families who possessed the corresponding temporal estates:

From 1582 to 1803, only a small number of new princes were given Reichsstand (that is, with a vote at the Reichstag):

A number of titles of prince were created for members of the counts' benches, but without ever receiving an individual vote at the Reichstag: Öttingen (14 Oct 1674), Waldeck (17 Jul 1682), Nassau-Saarbrucken (4 Aug 1688), Nassau-Usingen (4 Aug 1688), Nassau-Idstein (4 Aug 1688), Nassau-Weilburg (4 Aug 1688), Reuß-Greitz (1778), Lippe-Detmold (1789), Reuß-Schleiz (1806), Schaumburg-Lippe (1807). (Note that most of them became sovereign families after 1815). D. Imperial Cities The Imperial Cities (Reichsstädte) contained 51 cities, grouped in the Bench of the Rhine (14 cities) and the Bench of Swabia (37 cities). Their position in the Reichstag was not always clear; in particular, their ability to cast decisive votes, which was nevertheless confirmed in 1648. They had no say on certain matters: the admission of new States of the Empire, the investiture of imperial fiefs (as long as they were not affected), imperial wars (after 1803, when they gained the neutrality they had long requested). The presiding city was the one in which the Reichstag was held, which was always Regensburg after 1663. In 1803, 45 cities were mediatized, leaving 6 cities: Augsburg, Lübeck, Nürnberg, Frankfurt, Bremen, Hamburg. Augsburg and Nürnberg were absorbed by Bavaria in 1806. Frankfurt became a grand-duchy in 1810 but re-emerged with a minicipal government in 1813. Frankfurt was the seat of the Bund's assembly from 1816 to 1866; it was annexed by Prussia in that year. Lübeck was annexed to Schleswig-Holstein under the Nazis in 1937. At present, Bremen and Hamburg still exist as autonomous Länder in the Federal Republic of Germany, the last remnants of the Imperial cities. E. Composition of the Reichstag in 1521, 1755, 1792 The composition of the Reichstag at these three dates is fairly well known, because of three sources:

For the Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, Oestreich and Holzer have collated these three lists and determined which members appeared or disappeared between those dates, and why. The lists are presented in a separate page (in German).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||